10/4/2025

Building a game for the Game Boy with C and GBDK

The title screen of GB Yatzy, my first homebrew Game Boy game.

One of the things that has always appealed to me about programming is the idea of writing code that can run on all sorts of systems. For a while now, I've been kicking around the idea of developing a homebrew game for an old console. A project like this interested me for a few reasons:

- I could see my code run on a real system that predates me, or that I grew up playing.

- I could learn more about programming on more restricted devices, where limited memory and video capabilities meant making some careful choices.

- I could learn more about the process of debugging games for consoles.

I was interested in developing for the Game Boy since it had a monochromatic screen that made designing graphics easier for someone as artistically un-talented as myself, and because I knew a massive homebrew scene had sprung up in the last few years for the Game Boy and Game Boy Color. One reason for this was the release of the GB Studio toolkit that provided a drag-and-drop interface for developing homebrew games, which is frankly an incredible achievement. However, I wanted to get my hands a little dirtier, and have experience with something closer to the real development process. Some more research led me to GBDK, a really mature C library with a sizable community and legacy that seemed exactly like what I wanted. (Of course, this isn't quite the most realistic development experience I could have had, but I didn't have the tenacity for programming in assembly for a hobby project like this.)

The next question was what kind of game to make. In the spring of my senior year of college, some friends and I got really into playing Yatzy games when we were killing time, and I thought Yatzy was an ideal project for developing on a device with limited capabilities: its simple game state, lack of enemy players, and reduced visual elements meant that it would hopefully be somewhat straightforward to develop as a video game. It also seems that the Game Boy never got a Yatzy game, as the closest I could find was a combo pack that contained Hasbro's Yahtzee for the Game Boy Advance. So I settled on GB Yatzy as my first plunge into homebrew game development.

I had the idea for this project in May 2024, but it would be several months after graduation before I actually got started on this project, during a long, snowy weekend stuck indoors in January 2025. The result has been an insightful, occasionally maddening process that taught me a lot about C programming and Game Boy hardware.

Click here to download the ROM to play in a Game Boy emulator.

The perils of procedural programming

Nearly all of my programming experience so far has been object-oriented; I do most of my professional development in C#, and have worked in Java and C++ (from an object-oriented approach) in the past. For this project, however, I used pure C, and used a procedural approach to my code. The result, unfortunately, is kind of a mess. My instinct was to separate code into class-like structures: I had a file for maintaining game state, the dice onscreen, the UI, etc. But I didn't adequately compartmentalize some of these functions, so the functions within them often intermingle with each other with little structure. One tactic I tried was to prefix methods I wanted to be "public" (used by other files) with the file they belong to, while keeping methods I wanted to be "private" (within the file only) prefixed with an underscore, but again, inconsistency meant this system proved somewhat useless by the end of the project.

//private functions

void _printScoreDescription(void);

void _printScoreValue(void);

void _scoreSlotIndex_prev(void);

void _scoreSlotIndex_next(void);

void _lockScore(void);

// public functions

void points_reset(void);

void points_prepare(void);

void points_hide(void);

void points_calculateScore(void);

void points_handleInput(uint8_t current, uint8_t previous);An example of my "public" and "private" approach to method naming in my points.h file, which at least helped with readability.

Additionally, GBDK strongly discourages using lots of function parameters to keep function calls faster, so I had to rely on a lot of global variables. My instinct is to avoid global objects at all costs, so keeping up with how these global variables changed and interacted with each other quickly became difficult to keep track of. All of these factors together resulted in code that was more difficult to read and maintain than I would have liked, especially after taking a break on the project. However, I learned a lot about what not to do when structuring a project like this, and my hope is that the next procedural project I attempt will be far better structured.

One of my favorite aspects of the programming process was GBDK's emphasis on always specifying the size of variables. Always ssking myself questions like "can I fit this in an 8-bit integer, or will I need 16 bits" and taking advantage of overflowing unsigned integers made me feel like I had real control over my code and memory usage, and illustrated how programming was done in a more memory-limited environment. I don't get this experience as much with modern development, so it was really fascinating.

Game Boy graphics, no longer taken for granted

The limited, tileset-based graphics of the Game Boy held both advantages and disadvantages. Having only 3 colors + transparency to work with, as well as the standardized 8 pixels by 8 pixels of the tiles, meant that it was pretty simple to accomplish a readable, pleasant interface. On the other hand, the process of drawing tiles, then putting them in tilemaps, then loading all those tilemaps, quickly proved tedious. It made me appreciate the immense amount of effort that went into the far more complex games developed for retail in the Game Boy's heyday.

It was the graphics programming that really revealed how far game development tooling has come alongside the advancements in hardware. Effects that are simple in modern game programming required significantly more time and planning to pull off in this environment. For instance, without any ability to rotate tiles, drawing the spinning dice required two totally unique sets of tiles, that rapidly rotate back and forth. However, it also encouraged me to optimize as much as possible by reusing every corner tile I could, such as by making tiles for die faces 2 through 5 share corner tiles. Another was displaying text, which required loading all the letters in the VRAM and mapping them to the screen like any other, and I had to use an offset in my group of core tiles to account for these font tiles. I made a mistake by using an offset of 36 tiles instead of 37 in my tile indexes; luckily, I had left a blank tile in at the beginning of my tileset, so I solved this by loading the fonts at the start of VRAM after loading my own fonts.

void _initTiles(void)

{

// because I messed up and accidentally overwrote the 'Z' tile,

// I need to load my tiles before the font

set_bkg_data(36, NUM_CORE_TILES, core_tiles);

// load font

font_t min_font;

font_init();

min_font = font_load(font_min); // 36 tiles

font_set(min_font);

//...

}Loading my fonts after my own tiles, despite them being at the start of VRAM, to avoid having to redo all my own tile memory indexes.

I am very grateful for the various tools developed by the Game Boy homebrew community to make the graphics programming process easier. Some of the tools I used to develop the graphics for the game include:

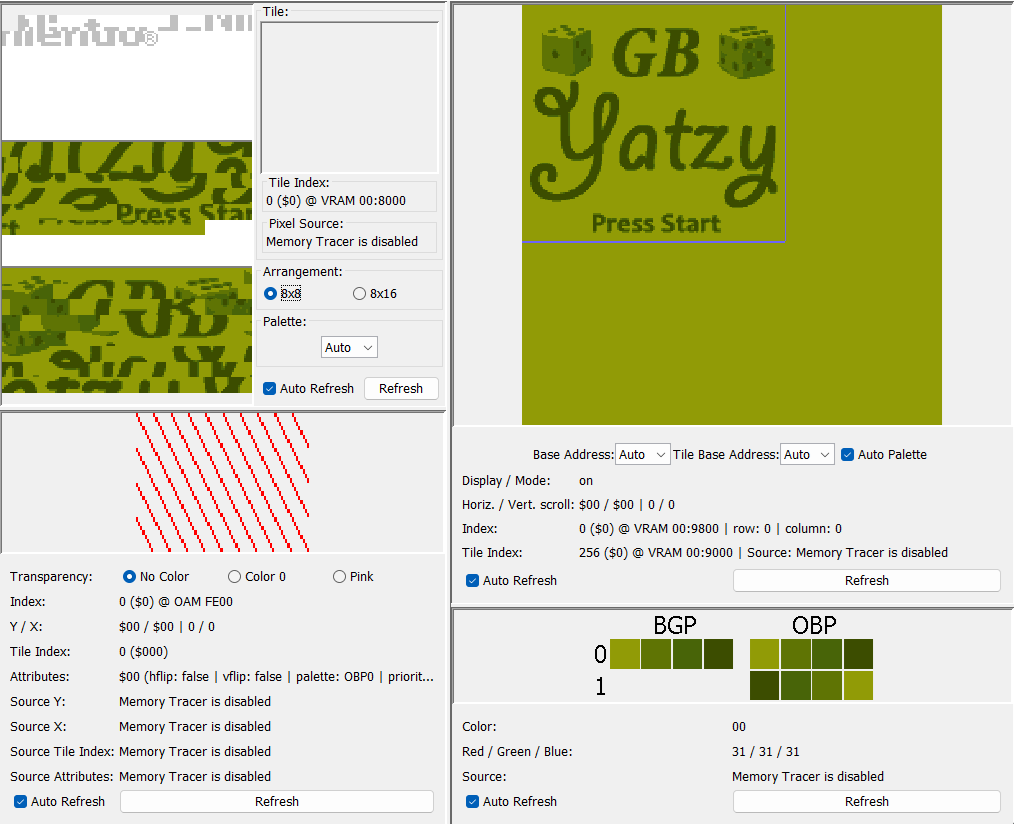

- Emulicious emulator, which offers an extension to integrate directly into VS Code's debugging tools. Being able to visualize which tiles were loaded into memory and their VRAM addresses, as well as the position of the window scroll and what the screen looks like outside of it, were immensely useful in the development process.

- Gameboy Tile Designer, which allows you to draw and export Game Boy tiles extremely easily. Nearly all of the custom tiles in the game were drawn with this program.

- Game Boy Color Image to Tiles Converter, which allows you to upload a PNG of 160x144 and get the corresponding tiles back. I found this later in the project when adding a title screen, and it let me make something way fancier than I would have had the patience for to hand-draw.

Emulicious debugger tools provide a ton of valuable insights into the VRAM and window.

The finish line (?)

Finally, one thing this project taught me was the challenge of staying disciplined when working on a hobby project such as this one. I got most of the development done in January, but took a short break when I got pretty close to being done - a break that ended up lasting for months. Returning to the code recently, I had a harder time remembering some of the intricacies of GBDK and my messy code. I was very glad past-me left detailed notes about what features and bug-fixes I had left to complete.

There's certainly plenty more I could add or improve in GB Yatzy. The most glaring omission is music, which I began to research briefly before deciding it wasn't what I was interested in learning. There's a lot of blank space on the screen that could probably be utilized for more exciting or pleasing graphics. There's no extra features for the Super Game Boy or Game Boy Color, and you can't save your high score between games to the "cartridge". There's also some weird movement of the cursor and arrow sprites when resetting games that I haven't quite solved.

Still, I'm really proud of the final product. This is the first major hobby project I've completed since starting my full-time software engineering career, and while it wasn't as smooth of a process I was hoping for, I learned a lot and accomplished something that I am excited to show to my friends. Firing the game up in an emulator and seeing the title screen pop up like any other Game Boy game is a rewarding feeling!